Wall Street Journal article states Credit Unions save members money

Credit Unions Draw More Car Loans — Not-for-profit cooperatives undercut banks, other lenders, offering lower rates

2022-12-28 07:07:31.872 GMT By Ben Eisen (Wall Street Journal)

There is still one place to get a good deal on an auto loan: credit unions. They have been offering some of the lowest rates around, undercutting banks and other lenders by a wide margin.

Auto lending is a bread-and-butter business for credit unions, and it isn’t unusual for them to beat the competition. But the extent to which they are doing so when rates are rising and other lenders are pulling back is drawing attention across the consumer-lending market.

In the third quarter, credit unions charged an interest rate of 5.94% on average for used cars, well below the 8.36% on offer from banks, according to credit-reporting firm Experian PLC. The gap was the widest in at least five years. For new cars, credit unions charged 4.43%, versus banks’ 6.06%. “They kept rates low when the rest of the market just exploded,” said John Toohig, who trades credit unions’ auto loans as head of whole-loan trading at Raymond James. Credit unions now have a bigger share of the auto-finance market than any other type of lender. In the third quarter, they held 28% of all auto financing, up from 20% a year earlier, according to Experian.

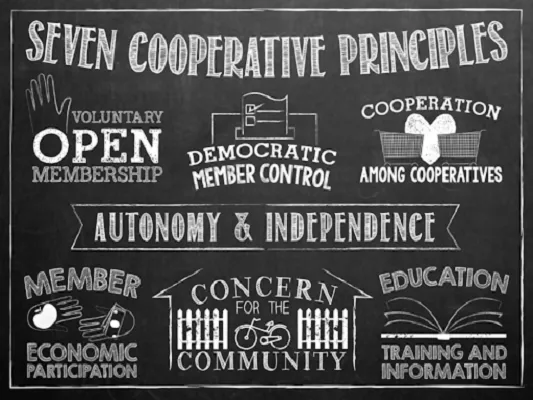

Some of the largest credit unions have added billions of dollars of auto loans to their books this year. SchoolsFirst Federal Credit Union grew its total auto loans by 29% in the first nine months of the year. Navy Federal Credit Union’s auto loans rose by 13% and Golden 1 Credit Union’s climbed by 18%, according to financial disclosures. Credit unions are not-for-profit cooperatives that are owned by their members and don’t pay federal income taxes. In recent years, they have grown rapidly, and in some corners of consumer finance they are going toe-to-toe with banks. Their profits funnel back to members, partly in the form of lower borrowing costs.

Free-lending credit unions could struggle in a recession that is expected next year. Americans might lose jobs and find themselves unable to pay their debts. Delinquencies on subprime auto loans have been climbing briskly in recent months, though analysts say credit-union loans have historically performed well.

Nick Honko, a doctor in Charleston, S.C., shopped around at banks when he was buying a new car over the summer, but “credit unions were just a ridiculous deal,” he said. At a friend’s recommendation, he went with Carolina Cooperative Federal Credit Union, which offered him 2.99% for an 84-month loan. He filled out much of the paperwork by hand and mailed it in. He opened an account to become a member and be eligible for the loan. Initially, he was able to use a credit card to make his loan payments and collect cash-back rewards, though he said the credit union later started charging for that option. Mr. Honko said the rate is so low that he earns more interest from stowing cash in his high-yield savings account that currently earns 3.3% than he pays in interest on the auto loan.

Credit unions weren’t as quick to jack up rates along with other lenders as the Federal Reserve lifted its benchmark rate to combat soaring inflation. Credit unions tend not to move in lockstep with capital markets, said Mr. Toohig. What is more, some credit unions have refocused on auto lending now that there is less demand for mortgages, according to William Hunt, senior analyst at Callahan & Associates, a credit union consulting and analytics firm. Unlike finance companies and the lending arms of auto makers, credit unions typically don’t pool auto loans into bonds and sell them to investors. Keeping loans on their balance sheets gives them flexibility to veer away from the rest of the market.

Credit union advocates also say that their lack of shareholders means they can focus on customers instead. “In a market where interest rates are going up, credit union loan rates will lag the market up, and then on the other side of the coin, savings yields will lead the market up,” said Mike Schenk, chief economist at the Credit Union National Association, a trade group. Banks are pulling back. Capital One Financial Corp. said its originations in the third quarter were down 28% from a year earlier. “Many auto lenders appear to have reflected rising interest rates in their marginal pricing decisions, but others have not, and they have gained market share and pressured industry margins,” Chief Executive Richard Fairbank told analysts in October.

Credit unions that find they need to sell auto loans to free up space on their balance sheet would likely take losses. That is because the interest rates on the loans are so far below going rates. Mr. Toohig said that some credit unions are finding that auto loans that traded at 101 or 102 cents on the dollar at the beginning of the year are now trading at 95 to 96 cents on the dollar.

When Jennifer Lapsker, a dentist in Albuquerque, N.M., was shopping for a new Tesla over the summer, the auto maker offered her a rate of about 4% for in-house financing. She wanted to do better, and had heard that credit unions offer the best rates. She walked into a nearby branch of Nusenda Credit Union and got a rate of 2.55% for a 60-month loan. She took delivery of the car in September. “I hadn’t heard of anyone getting a rate like that,” she said. “It seemed a little too good to be true, but I’m like, ‘I’m not going to question it.'”